The Quest for Cross-Lingual Systems

At Proxem, our clients ask us to extract information from e-mails, social medias, press articles, and basically any type of text you can imagine. In the standard case, the text to process is written in various languages. To establish systems that support a wide scale of languages and formats is one of the mission of our Research team.

Another goal of ours is to develop cross-lingual algorithms, that is algorithms which take as input texts in different languages and output an information computed on all those texts. For example on a task called sentiment analysis, which consists in detecting the "polarity" of a document ("is this document rather positive or negative?"), we want to implement a unique algorithm that would take as input sentences in English, Chinese, Spanish, etc and would compute a score. There are multiple reasons for us to aim at this. One is for simplicity sake. Indeed, we do not want to implement as many algorithms as languages we may have to handle. Another reason for that choice is that we want to leverage the important amount of available data for some languages to improve the accuracy on languages where data is rare.

A first step in this direction was to build a first representation layer that embeds words in a multidimensional space, which would then feed our algorithms. If you are familiar with word embeddings and especially its most famous implementation Word2Vec, well you must have realized that it is what we want :). Those "word vectors" have super nice properties:

the Euclidian distance works on them like a "semantic distance" in the sense that e.g "beautiful" is closer to "pretty" than to "algorithm", which make them far more interesting than traditional bag-of-words

they seem to capture semantic analogies such as "a is to b what c is to d": \[ \vec{king} - \vec{man} \approx \vec{queen} - \vec{woman} \]

they are learned in a completely unsupervised way.

From \( \vec{king} - \vec{man} \approx \vec{queen} - \vec{woman} \) to \( \vec{rey}_{es} - \vec{Mann}_{de} \approx \vec{regina}_{it} - \vec{femme}_{fr} \)

So word embeddings are a very good start. One property we would also like our word embeddings to have is that they conserve semantic distance throughout languages. For example, we want "pretty" to be close to "schön" in German and to "joli" in French.

In a recent paper that we presented at EMNLP'15 in Lisboa, we introduced a simple and scalable method to achieve this goal called Trans-Gram in reference to the Skip-Gram implementation from T. Mikolov. With this method we have aligned 21 languages in 2 and a half hours on CPU for 40-dimensional vectors and about 20 hours for 300-dimensional vectors.

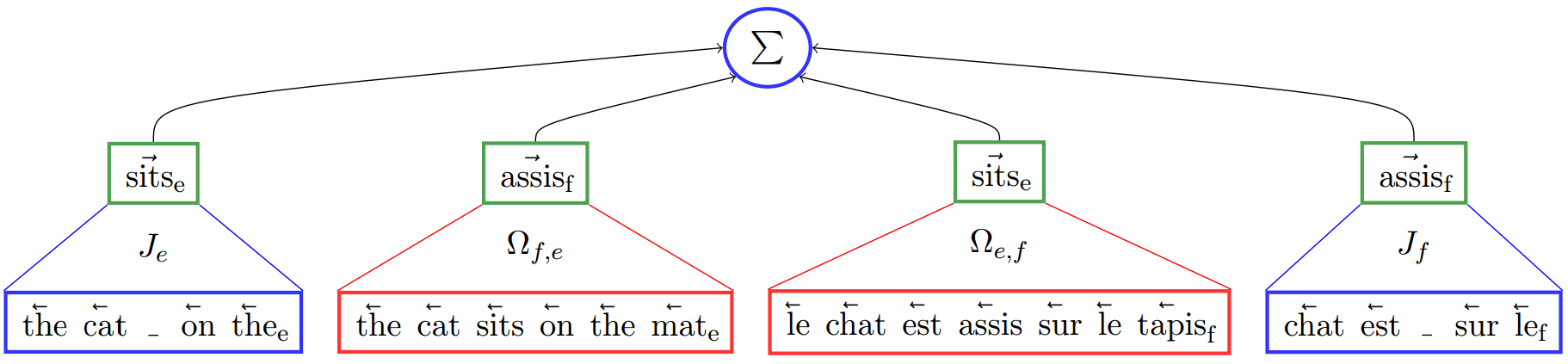

The core idea is to extend the Skip-Gram model to a multilingual setting. By analogy with Skip-Gram, the target word vectors are fitted to maximise their probability given their context, but here the source sentence is considered as the target word's context (and vice versa -- target sentence is a source word's context). Since the whole foreign sentence is considered as a context, there is no need in word-aligned data, any sentence-aligned parallel corpus can be used for training.

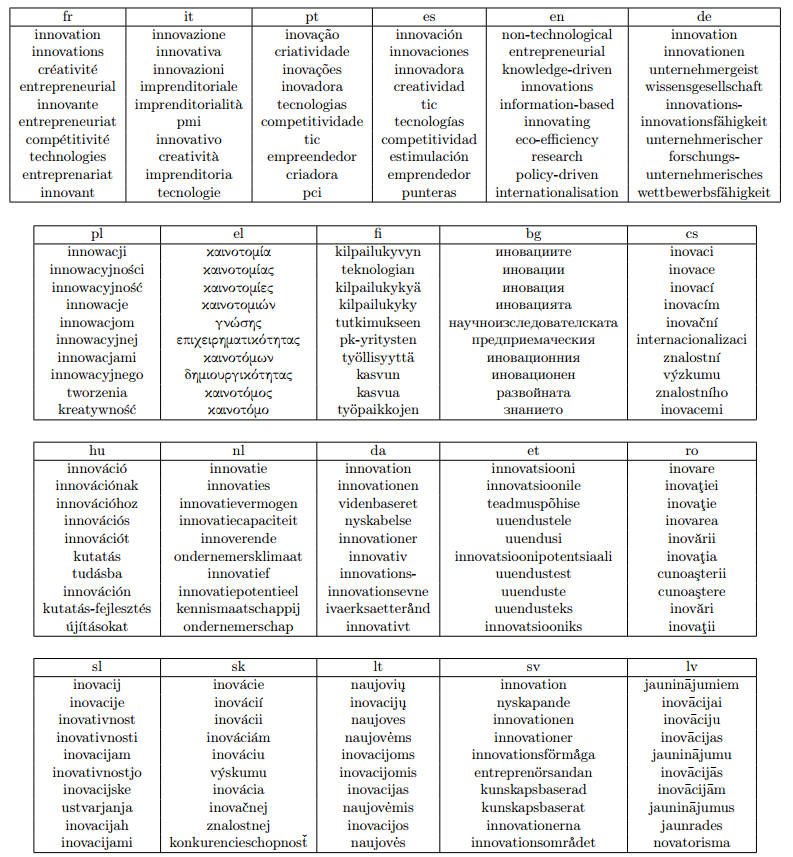

To illustrate our word vectors, we printed the top ten words closest to the word "innovation" in French:

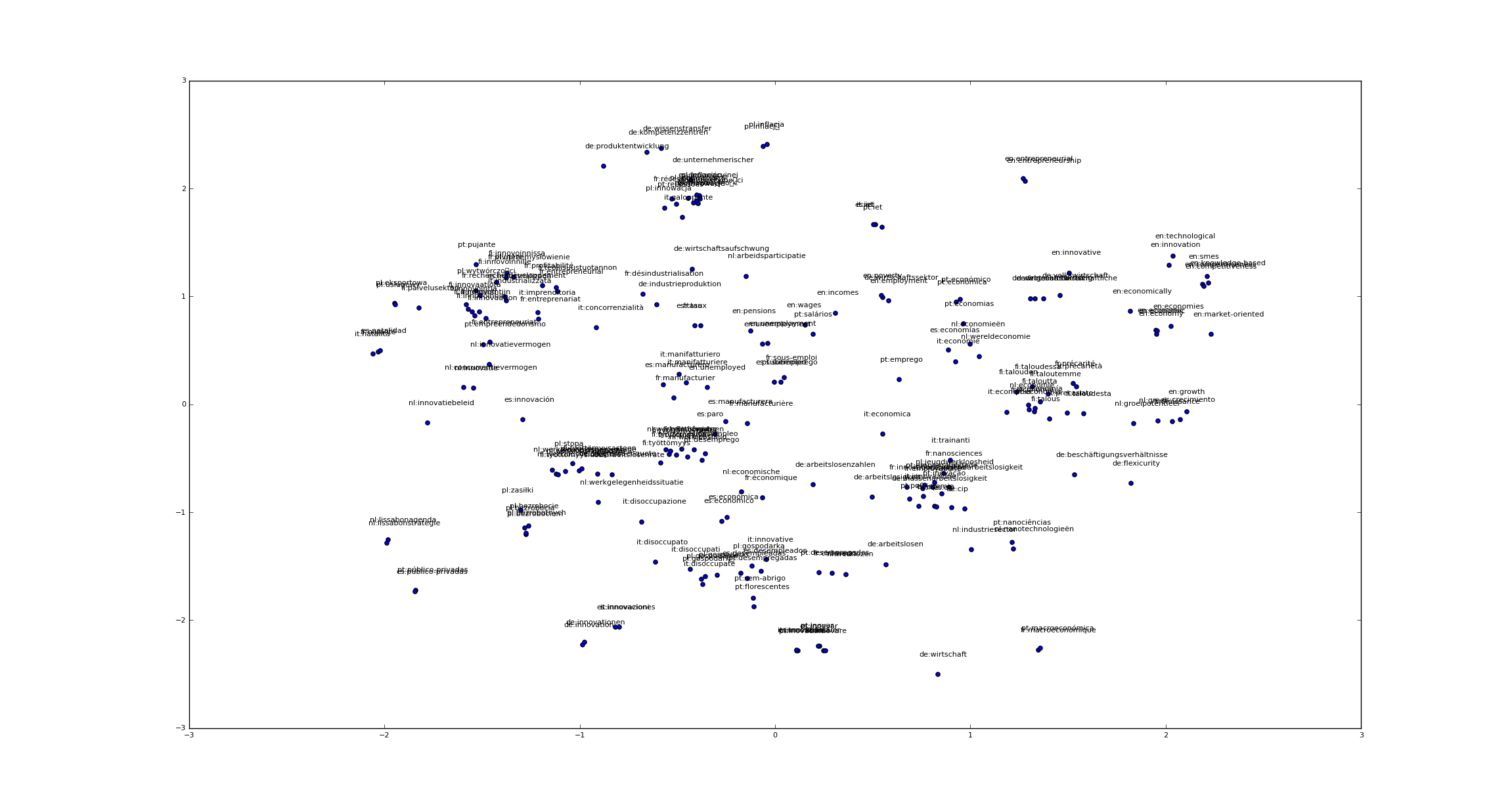

Here is also a tSNE that illustrate the alignement between words throughtout languages:

Interesting properties

We also demonstrate some useful properties of the cross-lingual word embeddings: their ability to discriminate between different word senses by combining vectors from different languages, and their ability to align the linguistic features across languages.

We call the first task “cross-lingual disambiguation”. The goal of this task is to find a suitable representation for each sense of a given polysemous word. The idea of our method is to look for a language in which the undesired senses are represented by unambiguous words and then to perform some arithmetic operation on their corresponding embeddings.

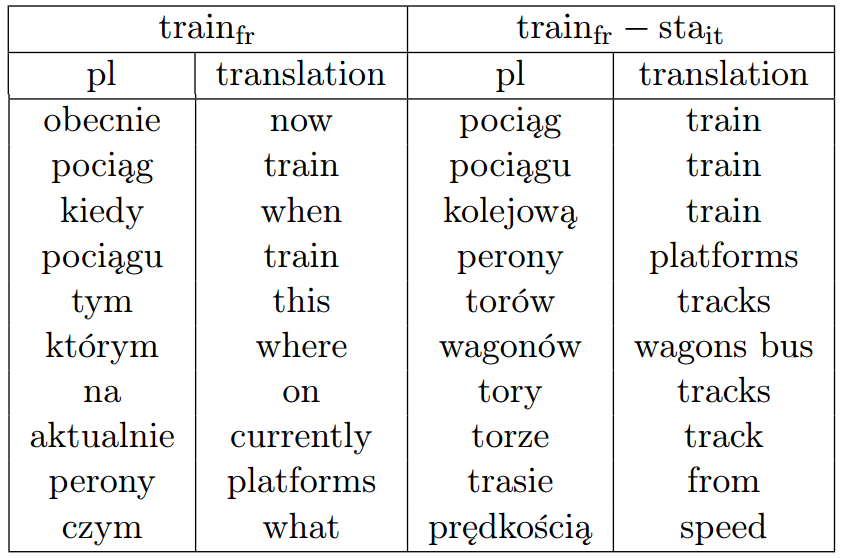

Let’s illustrate the process with a concrete example: consider the French word “train”. The three closest Polish words to \(\vec{train}_{fr}\) translate in English into “now”, “a train” and “when”.

This seems like a poor matching. Indeed, "train" in French is polysemous. It can refer to a line of railroad cars, but it can also be used to form progressive tenses. The French sentence “Il est en train de manger” translates into “he is eating”, or in Italian “sta mangiando”. As the Italian word “sta” is used to form progressive tenses, it’s a good candidate to disambiguate "train" in French. Let’s introduce the vector \( \vec{v} \approx \vec{train}_{fr} - \vec{sta}_{it} \).

Now the three Polish words closest to \(\vec{v} \) translate in English into “a train”, “a train” and “railroad”. Therefore \(\vec{v} \) is a better representation for the railroad sense of "train":

Another interesting property of the vectors generated by Trans-Gram is the transfer of linguistic features through a pivot language that does not possess these features. Let’s illustrate this by focusing on Latin languages, which possess some features that English does not, like rich conjugations. For example, in French and Italian the infinitives of “eat” are "manger" in French and "mangiare" in Italian, and the first plural persons are "mangeons" in French and "mangiamo" in Italian. Actually in our models we observe the following alignments: \( \vec{manger}_{fr} \approx \vec{mangiare}_{it} \) and \( \vec{mangeons}_{fr} \approx \vec{mangiamo}_{it} \). It is thus remarkable to see that features not present in English match in languages aligned through English as the only pivot language. We also found similar transfers for the genders of adjectives and are currently studying other similar properties captured by Trans-gram.

Some examples of cross-lingual systems that leverage aligned word embeddings

We use those word embeddings for our sequence-to-sequence labelling tasks such as Named Entity Recognitions, Part-of-Speech Tagging, etc. This allows us to transfer the information we have on certain languages to other languages, improving our performance on those tasks.

We also did some experiments on cross-lingual classification tasks. On the article, we trained a simple perceptron to classify articles from the Reuters RCV1/RCV2 corpora in German and English. There are four topics: CCAT (Corporate/Industrial), ECAT (Economics), GCAT (Government/Social), and MCAT (Markets). We train on English and infer on German and vice versa. We reported a 91.1% accuracy on the English to German task and a 78.7% on the German to English task, which was above the current state-of-the-art at that time.

We also trained a convolutional neural network for sentiment analysis on short product reviews from Amazon written in five languages: English, German, Spanish, French and Italian. The network trained indifferently on all those sentences. The only handcrafted feature that was given was the language of the sentence. Results are encouraging: we report internally a cross-validation accuracy superior to 85% with two classes (either positive or negative).

We use those systems to improve our product. The way we see it, all the verbatims no matter their language should be organized and displayed on the same interface and with the same taxonomy.

Yet, a limitation of word embeddings is that in order to extract global information about a sentence, one needs to expand from a good representation of a word to a good representation of a sentence, then to a paragraph, then to a document, then to a corpus... But that is yet another story :)